Linen History

Introduction to the History of Linen

The history of textiles production spans cultures and millenia. From the silkworms of ancient China to the cotton bolls of pre-Incan Peru, art and artifacts from prehistoric sites across the globe hint at the stories of early man’s first clever triumphs over nature. Radiocarbon dating of trace textile fibers found at prehistoric sites range from four to as many as thirty-four thousand years before present! But the oldest textile of them all—and the only one to inspire papal edicts and elaborate Roman courtroom antics—is linen.

Flax Fiber Varieties Affect the Feel of Linen

There are two varieties of flax fibers: shorter tow fibers used for coarser fabrics and line fibers used for finer fabrics. Flax fibers can be identified by their typical “nodes” which add to the flexibility and texture of the fabric. The cross section of the fiber is made up of irregular polygonal shapes which contribute to the coarse texture of the fabric. It can range from stiff and rough to soft and smooth.

Linen is Made from Flax

Linen is woven from the spun fibers of the flax plant, Linum usitatissimum. Flax grows wild in the region extending from Northern Africa to India and north to the Caucasus Mountains in Western Europe. Long before we lounged on sunny yacht decks on gauzy linen towels, prehistoric man was busy spinning these exceptionally-strong fibers into the simple thread that changed the world.

Oldest Textiles Discovered by Archaeologists are Flax Fibers

At an upper-Paleolithic excavation site at Dzudzuana Cave in the eastern-European country of Georgia, archaeologists discovered flax fibers that were preserved inside pollen chambers for 34,000 years. To date, they are the oldest evidence of manmade textiles ever discovered. The fibers at Dzudzuana showed evidence of having been knotted and dyed bright colors like turquoise and pink, consistent with the style of other artefacts left behind by our expressive ancestors.

Fast forward a few thousand years of evolution and innovation and we find, at an ancient site in eastern Turkey, a piece of 9,000 year-old, simply-woven linen cloth clinging to a bone tool—presumably once wrapped around the handle for a better grip. Archaeologist and ancient textile expert Gillian Vogelsang-Eastwood supposes this rudimentary fabric was produced on a crude loom of only four sticks, and woven in a manner derived from the already well-established practice of basket-weaving.

Woven Bags--A Serious Evolutionary Advantage

A simple piece of linen fiber or cloth might seem like rather un-exciting discoveries in the face of glittery riches from pharaohs’ tombs, but in fact they offer unparalleled insight into the evolution of the tools of early man.

Imagine yourself a caveman (or cavewoman) in prehistoric times. You live in a loosely-associated hunter-gatherer society, and venture out of your dark cave every morning in search of your daily sustenance. Just think how many more nuts and berries (or slabs of meat) you could carry if only you had a bag to keep them in instead of just your fists. Imagine the lightbulb light up: Oh, I could carry all these berries home if I wrap them up in my mammoth pelt, tie it shut and sling it over my shoulder! With enough food for the whole week, I’ll have all this free time to sit around and tame those wild dogs and invent the wheel!

The Taming of the Flax

Intentional cultivation of the wild flax plant likely began sometime between 5,000-4,000 BCE in the regions of North Africa and the Fertile Crescent, and from the beginning, linen was holy.

In ancient Mesopotamian city-states like Babylon and Ur, linen fabric was rare and accounted for only 10% of textile production. While the flax plant is not difficult to grow and reaches maturity in about 100 days, it also leaches most of the nutrients from the soil such that the fields must be let lie fallow for several years after a harvest. The laborious process of linen-making then took an additional 130-150 work days. Because production was so labor-intensive, only members of the elite like priests and royal figures could afford clothing and other articles made of linen. Cuneiform sources tell of thrones and statues of deities draped in bolts of fine linen inside temples.

Across the Sinai Peninsula not too many years later, the fertile Nile river valley provided a much more agreeable ecology for flax cultivation. The annual flooding of the Nile brought alluvial deposits that replenished the nutrients in the soil that had been depleted by the flax plant. Coupled with the surplus of the same slave labor that built the pyramids, flax quickly became ancient Egypt’s number one non-foodstuffs crop.

King Tut’s Favorite Fabric.

Unlike the Mesopotamians, the Egyptians prized linen fabric for much more than its exclusiveness. Linen fabric is durable, lightweight and wicks moisture away from sweaty skin. Linen thus became the favored material for clothing under the scorching desert sun, from the coarse linen garb of the slaves to the intricately-woven finery of the high priests.

Linen is also resistant to insects and microbial growth, and has a smooth, lint-free surface. Egyptians were obsessed with hygiene, so for these qualities, linen was considered pure. The whiter the fabric, the purer Egyptians believed it to be. By far, the greatest demand for linen was for ritual purposes.

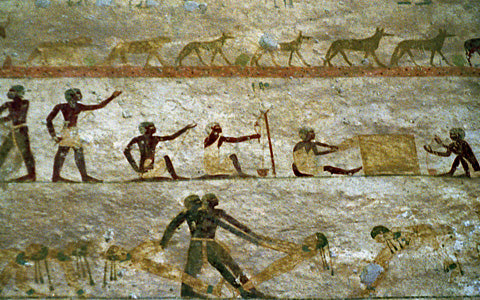

Priests were permitted to dress only in linen. “Chief Royal Bleacher” was an actual job title, though an unenviable one. Tomb paintings and models from across the region depict the repetitive process of washing the wet linen cloth, rubbing it with detergent, pounding it on a smooth stone with wooden clubs, rubbing the surface with balls of leather, rinsing, repeating, again and again; then finally laying it out to bleach dry in the hot sun.

One papyrus scroll describes:

the laundryman launders on the banks of the rivers, a neighbor of the crocodile...When he puts on the apron of a woman, then he is in woe...I weep for him spending the day under the rod.#

Indeed, Herodotus, a Greek historian who visited Egypt in the 5th century BCE, noted that

the people [of Egypt], in most of their manners and customs, exactly reverse the common practice of mankind. The women attend the markets and trade, while the men sit at home at the loom; and here, while the rest of the world works the woof up the warp, the Egyptians work it down.#

Upside down or rightside up, the linen woven in ancient Egypt has survived so many times over into our modern age that when we think of Egyptians and linen, we picture everything from white-linen-garbed slaves hauling gigantic bricks of limestone, to the toilet-paper wrappings of little boys’ Halloween costumes.

When the mummy of the boy-pharaoh Tutankhamun was unearthed in 1922 CE, portions of the linen wrappings that covered his remains were almost perfectly preserved, the hieroglyphed dates still legible despite the millennia.

The Rainbow Always Wins.

In keeping with our flamboyant prehistoric ancestors, linen boasts a way more colorful history than the whitest whites of the Nile Valley:

- The Romans conquered Egypt in the 4th c. BCE and they came with sword and beast--and dye, apparently. Pliny the Elder wrote in his Natural History of a contest held by Alexander the Great as he sailed the river Indus. The first man to attempt to dye linen, according to Pliny, he challenged his generals to a competition as to which man could most strikingly dye his linen sailcloth. He bade spectators judge from the banks of the river as the nautical parade sailed by. A few centuries later, he claims “Cleopatra had a purple sail when she came with Mark Antony to Actium”# and she sailed with the same purple sail as she fled.

- When Caesar was dictator of Rome in the 1st c. BCE, he ordered linen awnings, dyed blue and spangled with stars, stretched across the whole of the Roman Forum, so that “those engaged in lawsuits might resort there under healthier conditions.”

- Pliny also claimed to have witnessed what he called “incombustible linen,” grown in the ungodly heat of the Indian desert and, because of the extreme climate, grown impervious to fire. It was purportedly used for royal funerary shrouds, in order to keep the ashes of the corpse separate from those of the pyre.

- Even the Torah had something to say about this ubiquitous textile. Jewish law decrees: “do not wear Shatnez, wool and linen together” (Deuteronomy 22:11). Shatnez applies to garments made of yarn spun from both materials. At the time the law was written, pagan priests traditionally wore garments made of shatnez, and early scholars of the Torah, like Maimonides, believed this law served to prevent Jews from participating in Pagan rituals. However, the priest's girdle and the tzitzit worn by Orthodox Jews are preferably made of shatnez, and are thus exempt from the law. Modern Jewish scholars now believe that shatnez was thus perhaps a way of setting aside this fiber blend specifically for holy purposes, and linen only for those who could afford to buy it pure.

Weaving northward.

When the Romans fell, Egypt was conquered and ruled by a succession of Islamic dynasties in the 7th century CE. By this time, the industry of flax cultivation had spread throughout the Lower Countries of Europe. When Pliny wrote his Natural History in 77 CE, he made distinctions between different varieties of flax that were grown in different areas, each of which were known for producing linen suited for particular articles. In Spain they wove fishing nets, the Gallic provinces sailcloth, and Egyptian flax, he noted, “is not at all strong.”

Linen was produced en masse only in Spain and the rest of the Lower Countries of Europe until the 12th century, when France and Italy began using linen for tablecloths. Before the Middle Ages, the custom for formal dining was to recline while eating; as upright chairs and tables became more popular at meals, so evolved the tablecloth. People sitting around the table would use the edges of the linen to wipe their hands and faces in lieu of napkins, an act mothers around the world would chastise their children for today!

King Tut’s Favorite Fabric.

The Protestant Huguenot weavers fled religious persecution in France to more Northern countries in the 16th century, and they took with them their knowledge of flax cultivation and intricate linen-weaving techniques. Flax thrived in the cooler, damper climates, and the Huguenots continued to weave ornamental damasks that rivaled those of the Egyptians at which Pliny had marveled more than a thousand years prior.

The invention of the flax-spinning wheel in the 15th century made the handheld spinner obsolete, and two centuries later, a wheel operated by a foot-treadle left both hands free to spin. By that time, household items made of handwoven linen had become expensive status symbols of the elite. Napkins, towels, and table linens, often decorated with family crests and ornate themes of mythical or religious subjects, were woven to commemorate marriages and other special events.

In the 17th century, Ireland became known for weaving the finest of linen, and this reputation has persisted until present day. Because of the booming linen trade on mainland Europe and the relative ease with which one can cultivate flax, Irish farmers began to grow flax crops to supplement their incomes. The Irish harvest the flax plant before it reached maturity, which results in fibers that create very soft, fine thread. However, because the plant never matures, it also never produces any seeds to use for subsequent crops. The linen industry in Ireland thus remains, to this day, entirely dependent on the importation of flaxseed.

Flaxseed Sails the Ocean Blue.

When the tired, poor and huddled masses packed their worldly goods and flocked to the New World, the Irish packed their imported flaxseed. They weren’t the first to grow flax in the colonies--the Virginia Company had encouraged (unsuccessfully) the settlers at Jamestown to grow flax, and as early as 1626 the settlers of New Netherland were cultivating flax and shipping it back to Holland.

As more and more immigrants came to the colonies, there emerged at least a dozen different enclaves of linen production, each one reflective of the traditions its people brought with them from their homelands. They quickly learned that the warmer, drier North American climate grew a coarser and more brittle linen. Textiles produced in the warm Southern colonies were used mostly for rope, sailcloth and canvas; while the cooler Northern colonies produced finer linens.

Like the Irish, most rural farmers grew flax in addition to their other crops to supplement their income with the sale of the linen. They would, however, also keep a portion of the fabric produced for their own households for use as table linens, drapery, flour bags, burial sheets, and even wagon covers. Linen goods and bolts of fabric were used for trade in lieu of money. Akin to the barn-raising party, communities would organize “scutching bees,” where men and women alike would attend festivities centered around the monotonous tasks of flax processing--a merry way to organize rural labor.

In Ephrata, a Seventh Day Baptist town in Pennsylvania, the shorter tow fibers of the flax plant that are usually discarded during processing were used to manufacture paper, on which the community printed its local paper, the Ephrata Press.

Spinning into the Future.

The invention of mechanized spinning and weaving in the 19th century increased linen production exponentially. Everything from undergarments to bread-towels could be made more quickly and cheaply than ever before. The backbreaking burden of linen production thus fell from the shoulders of rural farmers into the more enduring metal arms of machines, and household items made of linen became more accessible to the lower classes.

In 1854 CE, when the Catholic Church reaffirmed the dogma of immaculate conception, Pope Piux IX even declared the Virgin Mary the patron saint of linen maids, in perhaps the first official fashion statement of the Vatican.

But it was not until after the 1970s, when the bulk of linen use shifted from household items to the apparel industry, that it became the perfectly-wrinkled fabric of expensive linen pants we love today. In fact, modern fashion designers make all sorts of claims about the amazing properties of linen fabric: it is moth and dirt-resistant, insect-repellent, cooling, durable, lint-free. Obviously the Egyptians agreed to the point that their holy men wore clothing made of no other fabric. What makes linen so amazing? Find out here!